It’s no secret that as we get older, concerns about health start to grow for many. Chronic disease statistics within the global population increase with age. By the age of 75, there is a 60% chance of having developed two or more chronic conditions. By 85 this increases to a 75% chance. Some of the common conditions people associate with getting old are osteoarthritis, type 2 diabetes, dementia, hearing loss and eye conditions including cataracts and glaucoma. One very important condition that affects millions of people every year around the world is osteoporosis. Considering it affects so many of us as we age, it’s not always up there at the fore-front of people’s minds as one to watch out for.

We’ve put together this blog to inform you fully on some of the facts and myths surrounding osteoporosis and to let you know why it’s so important to act early in life to avoid this potentially debilitating condition.

What is osteoporosis?

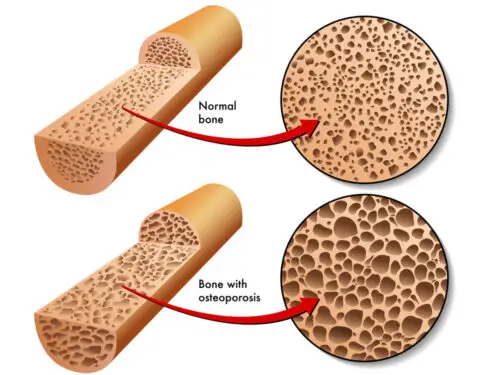

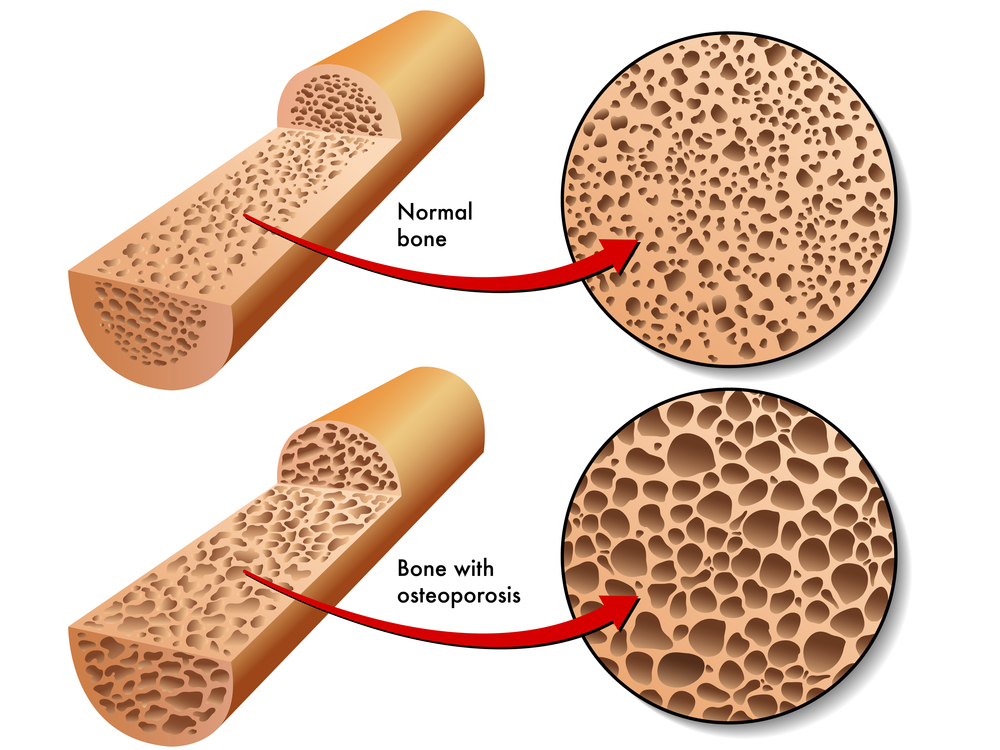

Osteoporosis is a condition that affects the density of bones of the skeleton causing them to become weak and fragile to breaks. It occurs when bones lose high amounts of protein and minerals, particularly calcium. The internal structure of the bone changes (i.e. the amount of bone that makes up the structure decreases) and this weakens the bone. The condition mainly affects the elderly population, but this is a condition that can take years to develop with lifestyle decisions early on in life playing a major role in its development in some people.

Myths and facts

Let’s outline some of the myths (and debunk them with facts!) surrounding osteoporosis. We believe a healthy population can only come from being an informed population.

- Osteoporosis only affects women: Stop right there! Yes, women are more susceptible to developing osteoporosis due to the hormonal changes they go through during menopause. The reduced production of oestrogen following menopause is one of the biggest risk factors for developing this condition because of the weakening affect it has on the bones. Make no mistake, men can also develop this condition. A fifth of men over 50 in the US will experience an osteoporotic bone fracture in their lifetime!

- Osteoporosis only affects Caucasians: Osteoporosis can affect anyone regardless of race or ethnic origin. The stats show there are higher numbers of cases in white than black people. Research suggests black people tend to develop a greater bone mineral density during the growth stage of life than white people, leading to overall stronger bones. It also suggests black people lose bone at a slower rate than white people as they age. This condition should however be taken seriously by all.

- Osteoporosis only affects the bones: Whilst osteoporosis primarily affects the strength of bones leading to increased fracture rates, this condition can affect the body in other ways as well. Recovery from hip fracture surgery due to a osteoporosis-related fall can be problematic and sometimes fatal due to other bodily complications such as immobility, heart and lung problems and increased infection rates following surgery.

- You’re only likely to fracture if you have a fall: Falling down is a common way people fracture bones, particularly if you have a low bone mineral density or osteoporosis. Unfortunately for people with severe osteoporosis, even the smallest of movements could lead to a bone fracture. Sneezing, reaching to pick up an object from the floor, stepping off a pavement onto the road or even a sudden change in direction whilst walking are all movements that may trigger a break in someone with this condition.

- Osteoporosis is painless: Many people believe that this condition is painless unless you physically fracture a bone. This may be true in the early stages of the disease as there may be no signs or symptoms of something changing in the bones until you experience your first fracture. As the disease progresses, chronic pain can be a big problem, particularly if there have been multiple fractures over the course of a person’s life. Osteoporosis is strongly linked with loss of muscle mass as we age, which leads to further deterioration of bone health. The body loses its ability to support the skeleton and various scenarios of pain states relating to posture and persistent pain following the healing of a fracture can exist.

- I’ll worry about osteoporosis if it happens: Take no chances. How you live your life in the early stages will affect your body later on. Children and adolescents need to be active and eat a healthy diet consisting of the right vitamins and minerals because it is at this stage of life where our bones build in mass and strength. Females reach their peak bone mass around the age of 18 and males reach it around 20 years of age. After this, we start to lose bone as the years progress. Staying active and being healthy throughout life will help to reduce the loss of bone that occurs with age. The rule is to act early (teach your kids the importance of being active) and continue to act as the years go by!

There is so much more we could discuss on this topic, but we’d be here all day! We hope this has given you a sound understanding of what osteoporosis is and the importance of acting early in life to avoid this condition. If you would like to know more, feel free to ask us next time you are in for a treatment or a chat, or check out Osteoporosis Australia. Stay safe everyone!

References

- National Osteoporosis Foundation. 2020. General facts. [Online]. Available from: https://www.nof.org/preventing-fractures/general-facts/. [Accessed 03 Sep 2020]

- GP Online. 2017. Comorbidities in older people. [Online]. Available from: https://www.gponline.com/comorbidities-older-people/elderly-care/article/1440520

- Hochberg, MC. 2007. Racial differences in bone strength. Transactions of the American Clinical and Climatological Association. 118. 305-315. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1863580/

Paolucci, T. et al. 2016. Management of chronic pain in osteoporosis: challenges and solutions. Journal of pain research. 9. 177-186. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4824363/